In most American history classrooms, children are taught that in 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue and “discovered America.” In this narrative, Columbus is portrayed as an adventurous explorer and a national hero. It is a narrative that is profoundly romanticized and even mythical, yet despite the historical records and accounts of Columbus’s heinous crimes against indigenous peoples, he is still glorified and honored in American history and culture.

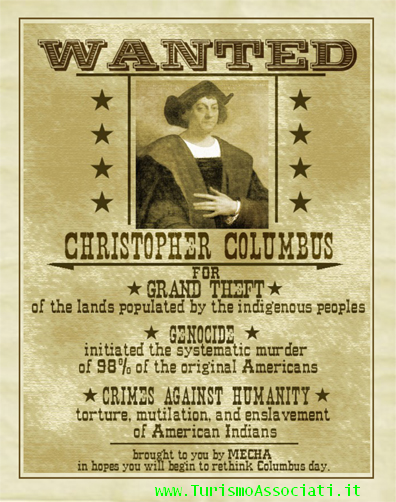

Heroificiation, as defined by author James W. Loewen, is a “degenerative process” that distorts reality and transforms “flesh-and-blood individuals into pious, perfect creatures without conflicts, pain, credibility, or human interest.” Christopher Columbus represents but one example in human history where an individual responsible for some of the most dreadful atrocities in our human history is molded into a savior-like figure and commemorated with a national holiday. It is disturbing how most American schoolchildren learn from history teachers and textbooks to not only venerate Columbus, but also to recite poems, sing songs, and perform in romanticized reenactments about his arrival to the Americas. These praises, accompanied with “Columbus Day” celebrations and parades, grossly gloss over the horrors of American Indian genocide initiated by Columbus’s expeditions.

American public schools rarely discuss Columbus’s atrocities. As Corine Fairbanks points out:

Recently, Roberta Weighill, Chumash, shared that her third grade son disagreed with his teacher about the Columbus discovery story and added that he knew Columbus to be responsible for the deaths of many Native people. The public teacher corrected him: “No. Columbus was just a slave trader.” Hmmm, just a slave trader? Oh! Is that all?

American history textbooks paint Columbus as a hero by treating his voyages into the “oceanic unknown” as exceptional and unique, as if he was the only explorer who ever journeyed to the Americas. Aside from the fact that indigenous peoples already lived in the land we now call the United States and weren’t waiting to be “discovered,” Columbus was not the first to set sail to the Americas. In his book, “Lies My Teacher Told Me,” Loewen provides a chronological list of expeditions that reached the Americas prior to Columbus, including explorers from Siberia, Indonesia, Japan, Afro-Phoenicia, Portugal, among other countries. Most of the eighteen high school history textbooks surveyed by Loewen omit the factors that prompted Columbus’s voyage in the first place: social change in Europe, advancement in military technology, use of the printing press – which allowed information to travel faster and further into Europe – and the ideological and theological rationalization for conquering new land. For example, Columbus’s greed and pursuit of gold in Haiti is either extremely downplayed or absent in textbooks. Columbus himself aligned amassing wealth with salvation, writing: “Gold is most excellent; gold constitutes treasure; and he who has it does all he wants in the world, and can even lift souls up to Paradise.” Accompanying Columbus on his 1494 expedition to Haiti was Michele de Cuneo, who wrote the following account:

After we had rested for several days in our settlement it seemed to the Lord Admiral that it was time to put into execution his desire to search for gold, which was the main reason he had started on so great a voyage full of so many dangers.

In elementary school, I remember learning that Columbus was peaceful to the indigenous people, who were in turn friendly and welcoming of the Spaniards. If anything was mentioned about war, it was always presented as, “There were good people and bad people on both sides.” Such an explanation shamelessly ignores the fact that “over 95 million indigenous peoples throughout the Western hemisphere were enslaved, mutilated and massacred.” The myth that Native Americans and Europeans were equally responsible for gruesome brutality was also reinforced in Disney’s animated feature, “Pocahontas.” The film placed Native American resistance and European violence on the same plane, i.e. the extremists on “both sides” made it bad for those who wanted peace, and colonialist domination and power was not a contributing factor to any form of resistance from the Natives. This distortion of history often likes to behave as sympathetic to Native Americans, but what it actually does is consistently depict them as “inferior” and “backwards,” while lionizing European colonizers and settlers, as well as constructing a history that is complimentary to the nationalism and pro-Americanism preached in most American schools.

I don’t think I would have learned about what Columbus really did if I didn’t start reading about Islamic history, which, too, was either ignored or vilified (especially during lessons on the Crusades) in my history classes. 1492, the same year Columbus sailed to the Americas, was also the year of the Spanish Inquisition, when Jews and Muslims were forced to convert or leave the country. The Catholic reconquest of Spain – the Reconquista – by King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella heightened interest in expanding European Christian domination, which led to their eventual agreement to sponsor Columbus’s voyage.

Upon his arrival to the Bahamas, Columbus and his sailors were greeted by Arawak men and women. Columbus wrote of them in his log:

They … brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells. They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features…. They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane… . They would make fine servants…. With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.

Worth noting is how Columbus’s description of the Arawak correlates with his sense of European entitlement and superiority. In several accounts, he praised the Arawak and other indigenous tribes for being hospitable, handsome, and intelligent, but not without saying they would make “fine servants.” When Columbus justified enslavement and his wars against the Natives, he vilified them as “cruel,” “stupid,” and “a people warlike and numerous, whose customs and religion are very different from ours.”

It is also important to understand the genocide of indigenous people could not have been possible without racism and sexual violence. Cherokee scholar and feminist-activist Andrea Smith cites Ann Stoler’s analysis of racism to illustrate the relationship between sexual violence and colonialism: “Racism is not an effect but a tactic in the internal fission of society into binary opposition, a means of creating ‘biologized’ internal enemies, against whom society must defend itself.” Racism marks the “other” as “inherently dirty,” and subsequently “inherently rapable.” For this reason, Smith argues that sexual violence is a weapon of patriarchy and colonialism, as opposed to being a separate issue altogether:

Because Indian bodies are “dirty,” they are considered sexually violable and “rapable,” and the rape of bodies that are considered inherently impure or dirty simply does not count. For instance, prostitutes are almost never believed when they say they have been raped because the dominant society considers the bodies of sex workers undeserving of integrity and violable at all times. Similarly, the history of mutilation of Indian bodies, both living and dead, makes it clear that Indian people are not entitled to bodily integrity.

Sexual violence and degradation of Native bodies is evident in how Columbus used Taino women as sex slaves and sexual rewards for his men. Columbus profited off of sex-slave trade by exporting them to other parts of the world. In fact, most of his income came from slavery. In 1500, he wrote to a friend: ”A hundred castellanoes (a Spanish coin) are as easily obtained for a woman as for a farm, and it is very general and there are plenty of dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to ten (years old) are now in demand.”

During an online conversation, some defended Columbus by arguing he was only carrying out the “norms of his time.” Justifying Columbus’s actions by the “standards” of his time, or through historical moral relativism, is problematic, not only because it dismisses genocide, sex slavery, and land theft, but also because it suggests there are overall honorable traits about Columbus and that he should be commemorated. For instance, Bartolome de Las Casas, the Spanish-born Dominican Bishop of Chiapas, witnessed and documented the horrors of Columbus’s subjugation, enslavement, and massacre of indigenous people. He is often quoted for writing:

What we committed in the Indies stands out among the most unpardonable offenses ever committed against God and humankind and this trade [in American Indian slaves] as one of the most unjust, evil, and cruel among them.

De Las Casas was absolutely mortified by the brutality he witnessed. In numerous accounts, he reports about Columbus commanding his men to cut off the legs of children who would run away; about Spaniards hunting and killing Natives for sport; about colonialists testing the sharpness of their blades on living, breathing Native bodies; about Columbus’s men placing bets on who would cut a person in half in a single sweep of their swords. De Las Casas wrote: “Such inhumanities and barbarisms were committed in my sight as no age can parallel. My eyes have seen these acts so foreign to human nature that now I tremble as I write.”

Although De Las Casas was strongly opposed to Columbus’s enslavement and dehumanization of Native peoples, his advocacy of indigenous rights and ending slavery was motivated by his desire to “convert and baptize the ‘heathen’ Indians.” In his debate with Juan Gines de Supulveda, who argued that the Natives were “barbarians” and predisposed to slavery, De Las Casas argued that they were intelligent and capable of attaining salvation in Christianity without coercion.

The point of mentioning De Las Casas is to show that, despite his missionary agenda, he was among Columbus’s contemporaries who were outraged and disgusted by his treatment of indigenous peoples. In other words, if the argument is that Columbus shouldn’t be judged by “today’s standards,” then we ought to judge him based on De Las Casas’ account. However, it is also quite unsettling that De Las Casas’ needs to be used in this manner – what does it say about the voices of Native Americans who live today and reflect on the genocide of their ancestors? Are their voices and accounts of Columbus’s atrocities not credible enough?

Also, what are “today’s standards”? Inherit in the romantic mythology of Columbus’s heroism is the white supremacist heteropatriarchal imperialism that colonizes, exploits, and unleashes massacres and sexual violence upon people in Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, and in parts of the world like Pakistan where war eerily operates as if there is no war, despite US military presence, airbases, drone assaults, political intervention, etc. Entire peoples are being vilified, demonized; their histories distorted, omitted; and Native Americans continue to resist and struggle against ongoing genocide that seeks to exterminate them. In fact, it is the logic of genocide, as Smith reminds us, that insists Native peoples must fade into nonexistence. War criminals are still glorified; war crimes are still justified; inhumane practices against humanity are still occurring in secrecy.

The Reconsider Columbus Day effort challenges the status quo, not just for the sake of restoring dignity and honesty to human history, but also for eradicating tyranny, colonialism, and imperialism that exists in the present. When American schoolchildren are taught to identify with Columbus, they are aligning themselves with an oppressor and making a racial distinction between “us” and “them.” The point of dismantling the way we celebrate and honor Columbus goes beyond exposing Columbus’s personality, it’s about taking responsibility for the ways we are complicit in reinforcing the logic of genocide. It’s about decolonizing ourselves in order to bring about radical, revolutionary change to society.

Decolonize for the sake of today, and for the sake of tomorrow.

Source: muslimreverie.wordpress.com