|

Di seguito tutti gli interventi pubblicati sul sito, in ordine cronologico.

Many physicists around the world are hard at work trying to figure out new and exciting ways to create ultra-cold objects, the reason being is that if a system could be created that operates at or at least very near absolute zero, superconductors could be devised that might help create quantum computers, which would of course run at speeds that would make the current generation look quaint. Plus, theory suggests new states of matter might be discovered.

Now, new work by a group of physicists from Harvard appears to be coming closer than ever. They’ve figured out a way to remove entropy from a specialized system leaving much colder atoms behind. In their paper, published in Nature, they discuss how they’ve come up with something called an orbital excitation blockade, a form of interaction blockade, to reach temperatures tens to hundreds of times colder than current methods.

The team did their research in a three step process. In the first they shot atoms that make up rubidium with a laser, forcing them to glow in a way that made them give off more energy then they absorbed, making them cooler of course. By doing so they also created a system whereby they were able to control the atoms due to the pressure created by the laser. Thus they could hold them still, move them around, or even cause them to run into each other.

Next, the team caused the atoms to grow even colder by allowing evaporative cooling to due its work.

After that, the real work began. Here the team used meshes of lasers, called optical lattices to remove entropy from the system. The already cooled atoms were made to knock into one another using lasers ala the method used to start the whole process; this time in the optical lattices. In so doing, the excited activity of atom one dampened the excited activity of the other, a process the team calls an orbital excitation blockade. The team then removed the excited atoms from the system, leaving the unexcited, cold atoms behind, in effect, removing entropy from the system.

In actual experiments done thus, far, the team has demonstrated an ability to actually remove heat from a system using their excitation blockade, but only to a certain point. They believe more research will allow them to reach temperatures tens or even hundreds of a billionth of a degree above absolute zero, which would take them into truly unknown territory.

More information: Orbital excitation blockade and algorithmic cooling in quantum gases, Nature, 480, 500–503 (22 December 2011) doi:10.1038/nature10668

Abstract

Interaction blockade occurs when strong interactions in a confined, few-body system prevent a particle from occupying an otherwise accessible quantum state. Blockade phenomena reveal the underlying granular nature of quantum systems and allow for the detection and manipulation of the constituent particles, be they electrons, spins, atoms or photons. Applications include single-electron transistors based on electronic Coulomb blockade7 and quantum logic gates in Rydberg atoms. Here we report a form of interaction blockade that occurs when transferring ultracold atoms between orbitals in an optical lattice. We call this orbital excitation blockade (OEB). In this system, atoms at the same lattice site undergo coherent collisions described by a contact interaction whose strength depends strongly on the orbital wavefunctions of the atoms. We induce coherent orbital excitations by modulating the lattice depth, and observe staircase-like excitation behaviour as we cross the interaction-split resonances by tuning the modulation frequency. As an application of OEB, we demonstrate algorithmic cooling of quantum gases: a sequence of reversible OEB-based quantum operations isolates the entropy in one part of the system and then an irreversible step removes the entropy from the gas. This technique may make it possible to cool quantum gases to have the ultralow entropies required for quantum simulation of strongly correlated electron systems. In addition, the close analogy between OEB and dipole blockade in Rydberg atoms provides a plan for the implementation of two-quantum-bit gates in a quantum computing architecture with natural scalability.

A Harvard University press release can be found below:

Physicists at Harvard University have realized a new way to cool synthetic materials by employing a quantum algorithm to remove excess energy. The research, published this week in the journal Nature, is the first application of such an "algorithmic cooling" technique to ultra-cold atomic gases, opening new possibilities from materials science to quantum computation.

"Ultracold atoms are the coldest objects in the known universe," explains senior author Markus Greiner, associate professor of Physics at Harvard. "Their temperature is only a billionth of a degree above absolute zero temperature, but we will need to make them even colder if we are to harness their unique properties to learn about quantum mechanics."

Greiner and his colleagues study quantum many-body physics, the exotic and complex behaviors that result when simple quantum particles interact. It is these behaviors which give rise to high-temperature superconductivity and quantum magnetism, and that many physicists hope to employ in quantum computers.

"We simulate real-world materials by building synthetic counterparts composed of ultra-cold atoms trapped in laser lattices," says co-author Waseem Bakr, a graduate student in physics at Harvard. "This approach enables us to image and manipulate the individual particles in a way that has not been possible in real materials."

The catch is that observing the quantum mechanical effects that Greiner, Bakr and colleagues seek requires extreme temperatures.

"One typically thinks of the quantum world as being small," says Bakr, " but the truth is that many bizarre features of quantum mechanics, like entanglement, are equally dependent upon extreme cold."

The hotter an object is, the more its constituent particles move around, obscuring the quantum world much as a shaken camera blurs a photograph.

The push to ever-lower temperatures is driven by techniques like "laser cooling" and "evaporative cooling," which are approaching their limits at nanoKelvin temperatures. In a proof-of-principle experiment, the Harvard team has demonstrated that they can actively remove the fluctuations which constitute temperature, rather than merely waiting for hot particles to leave as in evaporative cooling.

Akin to preparing precisely one egg per dimple in a carton, this "orbital excitation blockade" process removes excess atoms from a crystal until there is precisely one atom per site.

"The collective behaviors of atoms at these temperatures remain an important open question, and the breathtaking control we now exert over individual atoms will be a powerful tool for answering it," said Greiner. "We are glimpsing a mysterious and wonderful world that has never been seen in this way before."

Source: PhysOrg - via ZeitNews.org

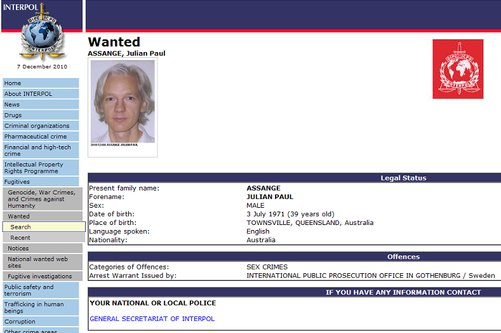

Julian Assange, founder and Editor-in-Chief of WikiLeaks, has been under house arrest, without charge, for almost 500 days. Over the past two months, his temporary home in the English countryside has played host to a series of extraordinary conversations with some of the most interesting and controversial people alive in the world today.

“The World Tomorrow” is a collection of twelve interviews featuring an eclectic range of guests, who are stamping their mark on the future: politicians, revolutionaries, intellectuals, artists and visionaries. The world's last five years have been marked by an unrelenting series of economic crises and political upheavals. But they have also given rise to the eruption of revolutionary ferment in the Middle East and to the emergence of new protest movements in the Euro-American world. In Julian's words, the aim of the show is “to capture and present some of this revolutionary spirit to a global audience. My own work with WikiLeaks hasn't exactly made my life easier”, says Assange, “but it has given us a platform to broadcast world-shifting ideas.”

For Julian, part of the show's strength lies in its “frank and irreverent tone”. “My conviction is that power can only be transformed if it is taken seriously – but ordinary people must resist the temptation to defer to the powerful."

The original music for the show has been composed by British-Sri Lankan artist M.I.A.

The first interview will be broadcast on RT on Tuesday 17 April, at 11:00 London time. Subsequent interviews, edited to last 26 minutes each, will be broadcast on a weekly basis. The interviews and transcripts will also be made available online. Arrangements are currently being made with other licensees to publish longer edits of the series. For more information on the show, please visit worldtomorrow.wikileaks.orghttp://worldtomorrow.wikileaks.org

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQs)

:: Who is producing “The World Tomorrow”?

The show is being produced by Quick Roll Productions, a company established by Julian Assange.

The main production partner is Dartmouth Films, a UK producer of independent films. Indispensable help and advice has been received from friends and supporters of WikiLeaks. If your network is interested in licensing the show, please visit the website of the distributor, Journeyman Pictures (http://www.journeyman.tv/63130/about-us/how-to-find-us.html).

:: What has RT got to do with “The World Tomorrow”?

RT is the first broadcast licensee of the show, but has not been involved in the production process. All editorial decisions have been made by Julian Assange. RT's rights encompass the first release of 26-minute edits of each episode in English, Spanish and Arabic.

:: Will the full material recorded during the interviews be made available?

We are devoted to making available as much material as possible within the constraints of Julian's circumstances. Longer edits of the episodes will be released in due course, and transcripts of the interviews will be published on the show's independent website, worldtomorrow.wikileaks.org. (http://worldtomorrow.wikileaks.org./)

:: Who is Julian Assange?

Julian Assange is an Australian-born publisher, entrepreneur and internet activist. He is the Editor-in-Chief of WikiLeaks, which he founded in 2006. Since then, WikiLeaks has been responsible for releasing the biggest leaks in history, including the Afghan (http://wikileaks.org/afg/) and Iraq (http://wikileaks.org/irq/) War Logs, the Collateral Murder Video (http://collateralmurder.com/), Cablegate (http://wikileaks.org/cablegate.html) and the Global Intelligence File (http://wikileaks.org/the-gifiles.html)s. Julian and WikiLeaks have received a number of awards for journalism and campaigning, including: The Economist Award for Freedom of Expession (2008), the Amnesty International Media Award (2009), the Le Monde Person of the Year (2010), The Sydney Peace Foundation Gold Medal (2011), the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism (2011) and the Walkley Award for Outstanding Contribution to Journalism (2011). He won the popular vote for TIME Person of the Year 2010.

:: What is the current status of Julian Assange?

As of Friday 13 April 2012, Julian has been under house arrest (http://justice4assange.com/), without charge, for 492 days. This follows on from his imprisonment in solitary confinement, also without charge, in December 2010. Julian is currently residing at a supporter's home in the English countryside, as dictated by his bail conditions. He is forced to wear an electronic manacle around his ankle at all times. Monitoring units are installed in the house and report to the British government via the security contractor, G4S (http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2011/mar/16/mubenga-g4s-face-charges-death).

A closed United States Grand Jury investigation into Julian Assange has been active in the USA for 574 days. Julian is currently awaiting the result of his UK Supreme Court appeal against his extradition to Sweden (http://www.swedenversusassange.com/). Information leaked to WikiLeaks from the email accounts of US private intelligence agency Stratfor (the “shadow CIA (http://english.al-akhbar.com/content/stratfor-wanted-assange-out-any-means)”), show that the United States government issued a sealed indictment (http://wikileaks.org/Stratfor-Emails-US-Has-Issued.html) against Julian Assange as early as January 2011.

More info: http://justice4assange.com/

:: What is the current status of WikiLeaks?

Despite 495 days of unlawful financial blockade (http://www.wikileaks.org/Banking-Blockade.html) by a cartel made up of VISA, Mastercard, the Bank of America, Western Union and PayPal, and despite severe restrictions on the liberty of Julian Assange, WikiLeaks is continuing its operations as normal, to the best of its abilities. On Monday 27 February 2012, WikiLeaks began publishing the Global Intelligence Files (http://wikileaks.org/the-gifiles.html), over five million emails from Texas-based “global intelligence” firm Stratfor. WikiLeaks is conducting its activities in conjunction with over ninety media partners all over the globe. A number of formal actions against the banking blockade are active in Europe and South America.

More info: http://wikileaks.org/Banking-Blockade

http://worldtomorrow.wikileaks.org/

http://justice4assange.com/

http://wikileaks.org

http://wikileaks.org/Banking-Blockade.html

Source: http://www.twitlonger.com/show/gunqv7

Con il Large Hadron Collider (Lhc) ci eravamo lasciati lo scorso dicembre: i tecnici del Cern di Ginevra avevano tra le mani una traccia da seguire per individuare la particella più ricercata al mondo, il bosone di Higgs (gli studi sono stati da poco sottoposti a varie riviste, tra cui Physics Letter B, da Atlas e Cms). Da anni gli scienziati cercano di provare l'esistenza di questa entità subatomica necessaria per avvalorare la teoria del Modello Standard sull'origine di tutta la materia che occupa l'universo. Ebbene, giusto in questi giorni Lhc torna in piena attività per raccogliere nuovi dati. Ma stavolta i fisici faranno toccare un nuovo record all'acceleratore, alimentandolo con 4 teraelettronvolt (TeV). E intanto gli scienziati il 15 febbraio alle ore 19:00 faranno una chiacchierata con gli internauti su Google+, in diretta dalle profondità di Ginevra. Per partecipare basta avere un profilo sul social netwok e aggiungere +Cms Experiment alle proprie cerchie. Qui i dettagli.

Come spiega Wired.co.uk, l'energia di collisione utilizzata per il prossimo ciclo di esperimenti di Lhc è stata innalzata del 14% rispetto ai valori del 2011. Una scelta tecnica dettata dal fatto che a partire dal prossimo novembre l' acceleratore dovrà restare chiuso per 20 mesi in attesa di avviare ulteriori esperimenti nel 2015. A partire dalle prossime settimane, i fisici del Cern potranno così raccogliere preziosi dati utili ad approfondire la natura del bosone.

Infatti, l'immensa mole di risultati ottenuti dagli esperimenti del 2011 non ha ancora permesso agli scienziati di dare una risposta chiara all'interrogativo che li assilla da più di 50 anni: quale sia la massa del bosone di Higgs. Finora i fisici hanno utilizzato Lhc per far scontrare fasci di protoni a altissima velocità nella speranza di poter osservare anche solo per un istante una piccola traccia dell'esistenza della particella fondamentale.

Dall'analisi dei dati raccolti lo scorso anno i ricercatori avevano individuato qualche segnale interessante intorno ai valori di riferimento di 125 gigaelettronvolt (GeV), ma si erano anche imbattuti in una nuova particella subatomica simile al bosone chiamata Chi_b(3P). Insomma, solo aumentando il numero di collisioni i fisici possono sperare di imbattersi per la prima volta in una traccia inconfutabile. Ecco perché, come suggerisce Scientific American, il Cern ha voluto premere sull'acceleratore Lhc per ottenere il 30% di dati in più.

Fonte: Wired.it

Zona responsabila cu aceasta activitate se afla, de fapt, la trei centimetri de centrul creierului, distanta pe care specialistii o considera uriasa.

Acum, oamenii de stiinta au anuntat ca aproape toate imaginile din manualele de biologie si de pe internet, care indica zonele creierului, sunt gresite. Mai mult, noile descoperiri sugereaza ca exista asemanari mult mai mari decât se credea, între creierul uman si cel al maimutelor. Daca pâna acum, ceea ce ne deosebea de rudele noastre apropiate erau tocmai acesti "centri ai vorbirii", cercetarile indica faptul ca lucrurile nu stau chiar asa.

Multa vreme s-a crezut ca vorbirea umana este procesata în partea din spate a cortexului cerebral, în apropierea ariei auditive, într-o regiune numita aria Wernicke. Acum, însa, expertii au analizat mai bine de 100 de studii de imagistica medicala si au ajuns la concluzia ca aria Wernicke nu se afla acolo unde se credea. De fapt, se pare ca ea se afla cu trei centimetri mai aproape de lobul frontal si pe partea opusa a cortexului auditiv.

Descoperirea este cu atât mai importanta cu cât noua localizare a zonei Wernicke este similara cu cea aflata în creierul maimutelor. Prin urmare, centrii umani responsabili cu vorbirea sunt asemanatori cu cei ai maimutelor. De asemenea, noile cercetari ajuta la o mai buna diagnosticare a pacientilor. Daca cineva are probleme de întelegere a unui discurs sau daca nu poate sa vorbeasca, atunci specialistii ar trebui sa cerceteze o alta zona.

Cercetarea a fost realizata pe 115 studii de imagistica, care au inclus peste 1.900 de participanti si au identificat peste 800 de coordonate care indicau locul în care se proceseaza vorbirea. Rezultatele au indicat ca aria Wernicke se gaseste în lobul temporal stâng, mai exact în girusul temporal stâng, în fata cortexului auditiv primar.

Sursa: Daily Mail - via Descopera.ro

The discovery will help understanding of other protein-folding disorders such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases, as well. Findings are featured as the cover story in the current issue of Chemistry & Biology.

People born with Fabry disease have a faulty copy of a single gene that codes for the alpha-galactosidase (?-GAL) enzyme, one of the cell's "recycling" machines. When it performs normally, ?-GAL breaks down an oily lipid known as GB3 in the cell's recycling center, or lysosome. But when it underperforms or fails, Fabry symptoms result. Patients may survive to adulthood, but the disorder leads to toxic lipid build-up in blood vessels and organs that compromise kidney function or lead to heart disease, for example.

The faulty gene causes its damage by producing a misfolded protein, yielding an unstable, poorly functioning ?-GAL enzyme. Like origami papers, these proteins are unfolded to start and only become active when folded into precise shapes. At present, enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) is the only FDA-approved treatment for such lysosomal storage disorders as Fabry, Pompe and Gaucher diseases, but ERT requires a complicated and expensive process to purify and replace the damaged ?-GAL enzyme, and it must be administered by a physician.

The alpha-galactosidase enzyme (yellow) is shown binding to the pharmacological chaperone DGJ (colored). The key interaction responsible for the high potency of DGJ is marked with an arrow at right. Credit: Graphic courtesy of Scott Garman at UMass Amherst

Instead of replacing the damaged enzyme, an alternative route called pharmacological chaperone (PC) therapy is currently in Phase III clinical trials for Fabry disease. It relies on using smaller, "chaperone" molecules to keep proteins on the right track toward proper folding, but their biochemical mechanism is not well understood, says Garman.

Now, he and colleagues report results of a thorough exploration at the atomic level of the biochemical and biophysical basis of two small molecules for potentially stabilizing the ?-GAL enzyme. He says their use in PC therapy could one day be far less expensive than the current standard, ERT, and can be taken orally.

This work, which improves knowledge of a whole class of molecular chaperones, represents the centerpiece of UMass Amherst student Abigail Guce's doctoral thesis and was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Other members of the team are graduate students Nat Clark and Jerome Rogich.

"The interactions we looked at are exactly the things occurring in the clinical trial right now," Garman says. Further, "the same concept is now being applied to other protein-folding diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. Many medical researchers are trying to keep proteins from misfolding by using small chaperone molecules. Our studies have definitely advanced the understanding of how to do that."

In their current paper, Garman and colleagues compare the ability of two small chaperone molecules, galactose and 1-deoxygalactononjirimycin (DGJ) to stabilize the ?-GAL protein, to help it resist unfolding in different conditions such as high temperature and different pH levels.

They found that each chaperone has very different affinities: DGJ binds tightly and galactose binds loosely to the ?-GAL, yet they differ in only two atomic positions. "Tight is better, because you can use less drug for treatment," Garman says. "We now can explain DGJ's high potency, its tight binding, down to individual atoms."

In earlier studies as in the current work, the UMass Amherst team used their special expertise in X-ray crystallography to create three-dimensional images of all atoms in the protein to understand how it carries out its metabolic mission. They also found a new binding site for small molecules on human ?-GAL that had never been observed before.

Crystallography on the two chaperones bound to the ?-GAL enzyme showed that a single interaction between the enzyme and DGJ was responsible for DGJ's high affinity for the enzyme. Other experiments also showed the ability of the 11- and 12-atom chaperones to protect the large, 6,600-atom ?-GAL from unfolding and degradation.

For the first time, by making a single change in one amino acid in protein, they forced the DGJ to bind weakly, indicating that one atomic interaction is responsible for DGJ's high affinity.

"It was surprising to find these two small molecules that look very much the same have very different affinities for this enzyme," says Garman, "and we now understand why. The iminosugar DGJ has high potency due to a single ionic interaction with ?-GAL. Overall, our studies show that this small molecule keeps the enzyme from unfolding, or when it unfolds, the process happens more slowly, all of which you need in treating disease."

Source: University of Massachusetts at Amherst - via ZeitNews.org

Oggi grazie alla biologia molecolare gli scienziati hanno sviluppato strumenti di analisi così potenti e veloci da realizzare test genetici a soli mille dollari. Ma tutto ciò non sarebbe mai stato possibile senza lo sforzo dello Human Genome Project (Hgp), il consorzio internazionale che ha permesso di sequenziare il genoma umano. E pensare che i fondi stanziati nel 1990 ammontavano a ben 3 miliardi di dollari. Soldi spesi davvero bene, visto che i primi risultati sono stati pubblicati su Nature il 15 febbraio 2001 in un numero open access.

Una conquista senza precedenti nella storia della genetica dopo la scoperta del dna, la molecola alla base della vita. In origine, gli scienziati si aspettavano di concludere lo Hgp nell'arco di 15 anni, ma la prima bozza pubblicata nel 2001 dimostrò a tutti che il lavoro sarebbe stato completato in anticipo sulla tabella di marcia. Infatti, dopo la pubblicazione della bozza su Nature – che copriva l' 83% del genoma – i risultati definitivi furono annunciati già nel 2003. Merito del lavoro di una équipe instancabile di ricercatori provenienti da tutto il mondo, che in una decina di anni ha analizzato quasi tutte le 3 miliardi di molecole ripetute (A, C, G, T) che compongono il nostro codice genetico. In tutto, gli scienziati hanno identificato circa 23mila geni che codificano proteine, ma questi non rappresentano che l'1,5% di tutto il genoma. Insomma, il nostro dna è molto di più che un semplice libretto di istruzioni. Sta di fatto che le ricerche sono andate avanti per altri anni, e oggi online è disponibile una sequenza aggiornata al 2009.

La cosa più interessante è che il materiale genetico su cui hanno lavorato gli scienziati dello Hgp proveniva per il 70% da un unico donatore anonimo originario della cittadina americana di Buffalo. Una scelta del tutto casuale dovuta al fatto che il campione di dna prelevato dal misterioso individuo era il meglio conservato tra tutti quelli delle altre migliaia di volontari che si erano offerti.

Ma esiste anche un'altra persona che ha avuto molto a che fare con il sequenziamento del genoma umano, e il suo nome è tutt'altro che sconosciuto. Si tratta di Craig Venter, lo scienziato-businessman che nel 1998 ha fondato Celera, una company di biotecnologie specializzata nel sequenziamento della molecola a doppia elica. Venter, che fino a qualche anno prima aveva partecipato a Hgp, si era messo in proprio con lo scopo di battere sul tempo il consorzio internazionale e trarne lauti profitti. La sua idea iniziale era quella di investire 300 milioni di dollari nell'impresa per poi brevettare parte dei geni sequenziati.

Così, in una corsa contro il tempo, gli scienziati dell'Hgp si affrettarono a rendere pubbliche parte delle sequenze genomiche codificate fino a quel momento. Il team di bioniformatici dell'università californiana di Santa Cruz mise online una prima bozza il 7 luglio 2000. Da quel giorno, il genoma umano era diventato di pubblico dominio.

Fonte: Wired.it -

A volta basta davvero poco a far capitolare il partner. Niente complessi corteggiamenti o danze sensuali: per alcuni bachi da seta è sufficiente lasciare nell’aria qualche goccia del loro profumo (molecole di feromone) per attrarre i maschi, anche a chilometri di distanza. Una questione di chimica insomma, cui probabilmente neanche la specie umana sarebbe immune.

In realtà, stabilire il ruolo che i segnali chimici hanno nell’essere umano non è affatto facile, anche se esistono indizi a sostegno di una comunicazione “sotto il livello della consapevolezza”, come spiega Bettina Pause della Heinrich Heine University di Düsseldorf, che ha dimostrato la capacità della specie umana di sentire un segnale d’allarme nell’odore delle persone impaurite o ansiose. Una sorta di feromoni umani in altre parole, non tutti volti al corteggiamento del partner, spiegano gli scienziati; così come avviene in natura, con feromoni emessi durante i combattimenti (dai lemuri) o solo per indirizzare i propri simili verso le fonti di cibo, come fanno le formiche.

D’altronde, come riporta Scientific American, basta pensare agli effetti di una convivenza stretta, quale può essere la condivisione di una stanza. In questi casi infatti a volte si osserva che la forte vicinanza porta a sincronizzare il ciclo mestruale delle ragazze. Mentre è sufficiente far annusare gli odori prodotti dalle ascelle (maschi e femmine) ad alcune donne per variare il loro ciclo; ma la molecola (o le molecole) responsabili di questo cambiamento non sono state ancora identificate.

Ma senza ricorrere a esperimenti, c’è un comportamento innato guidato dalla chimica, come spiega Charles Wysocki, della Monell Chemical Senses Center di Philadelphia. Quello che porta un neonato a trovare il seno della madre in cerca di cibo, seguendo dei segnali chimici provenienti dal suo capezzolo. D’altra parte, come spiegano gli scienziati, alcuni odori emessi dal seno di donne che allattano avrebbero effetti anche sugli adulti, aumentando per esempio il desiderio sessuale nelle donne senza figli. Per ora però la ricerca dei feromoni umani resta senza veri e propri protagonisti, eccezion fatta per l’ androstadienone (derivante dal testosterone), la molecola in grado di rendere le donne più rilassate.

Ma oltre a cercare chi comunica cosa, l’altra parte del problema sull’esistenza o meno di feromoni umani riguarda l’identificazione della struttura responsabile a percepire l’odore e il segnale che esso veicola. Negli animali a farlo è l’ organo vomeronasale, una struttura collocata nel naso, non sempre presente nell’essere umano o comunque presente con funzioni ridotte (ovvero i geni che codificano per i recettori non sono attivi). Ragion per cui spiegare come la specie umana percepisca i feromoni sembrerebbe un’impresa alquanto ardua. Se non fosse che uno studio lo scorso anno ha mostrato come l’ androstadienone sia in grado di indurre una risposta a livello cerebrale in alcune persone, anche in assenza dell’organo vomeronasale (o comunque presente, ma bloccato). A dimostrazione quindi che l’essere umano riesce a captare tali segnali chimici, feromoni, attraverso il sistema olfattorio (o forse anche attraverso il misterioso nervo terminale o nervo cranico 0).

Feromoni a parte, ci sono altre molecole che contribuiscono all’odore di una persona e che ci aiutano a stabilire incoscientemente se ci piace o meno. Sono le proteine del complesso maggiore di istocompatibilità (MCH), che svolgono ruoli importanti a livello immunitario. E che, secondo alcuni studi, sarebbero alla base delle nostre scelte sessuali. In particolare ci piacerebbero di più quelli con MHC particolarmente diversi dai nostri: un espediente trovato dall’evoluzione. Il motivo? Perché scegliendo MHC diversi dai nostri, quelli dei nostri figli lo saranno ancora di più. A beneficio del loro sistema immunitario.

Fonte: Wired.it

Acum, dupa 85 de ani, experimentul nu a ajuns nici macar la jumatate.

Parnell, profesor la Universitatea din Queensland, Australia, a topit niste smoala pe care a lasat-o la racit timp de trei ani, iar apoi a pus-o într-o pâlnie fixata deasupra unui pahar. Prima picatura de smoala a curs dupa opt ani, iar cea de-a doua dupa alti noua ani. Initiatorul experimentului nu a mai apucat sa vada si cea de-a treia picatura (care s-a scurs în 1954), el stingându-se din viata în 1948.

Dupa moartea lui Parnell, echipamentul a fost pus într-un dulap de unde a fost scos în 1961, de catre profesorul John Mainstone. În 1975, acesta convinge conducerea universitatii sa permita expunerea publica a experimentului. Astazi, cercetarea poate fi urmarita în timp real, deoarece o camera web transmite zilnic imaginile catre lumea întreaga.

Cea mai recenta picatura s-a scurs în pahar acum 12 ani, însa momentul nu a fost imortalizat din cauza unei defectiuni a camerei. Specialistii se asteapta ca urmatoarea picatura sa cada în cursul anului viitor.

Puteti urmari experimentul aici.

Sursa: Engadget - via Descopera.ro

While fuel cells show a lot of promise for cleanly powering things such as electric cars, there's something keeping them from being more widely used than they currently are - they can be expensive. More specifically, the catalysts used to accelerate the chemical processes within them tend to be pricey. Work being done at Finland's Aalto University, however, should help bring down the cost of fuel cells. Using atomic layer deposition (ALD), researchers there are making cells that incorporate 60 percent less catalyst material than would normally be required.

In a fuel cell, the anode is coated with noble metal powder, which serves as a catalyst by reacting with the fuel. Using their ALD method, the scientists were able to use less powder to create a coating that was thinner and more even than conventional coatings, yet just as effective.

While fuel cells can be made with a number of different fuels (even including microbes or coal) and noble metals, the Aalto team is now developing low-cost cells that will run on methanol or ethanol, with a palladium catalyst. Probably the most well-known fuel cells are those that run on hydrogen, but such cells require a catalyst made of platinum, which is twice the price of palladium.

A paper on the research was recently published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry C.

Source: Gizmag - via ZeitNews.org

Si addicono all’inverno le ultime rivelazioni del telescopio spaziale Planck: una mappa delle gelide nubi molecolari (a partire dall’emissione di monossido di carbonio della Via Lattea) e la conferma dell’esistenza della cosiddetta foschia galattica, insieme alle prime indiscrezioni sulla sua natura. I nuovi risultati della sonda dell' Agenzia Spaziale Europea sono stati presentati a Bologna in occasione del convegno internazionale Astrophysics from the radio to submillimetre – Planck and other experiments in temperature and polarization, e sono frutto di un attento lavoro di pulizia dei dati (prima del quasi pensionamento dello strumento).

Missione principale di Planck, al lavoro dal 2005, è infatti studiare la cosiddetta radiazione cosmica di fondo, eco di un passato distante 13,7 miliardi di anni, epoca del Big Bang. Tuttavia, per poter isolare questa radiazione occorre eliminare tutti i segnali che arrivano dalle altre sorgenti di primo piano (foreground), anch’esse registrate dai sofisticati strumenti che si trovano a bordo del telescopio. Tra queste ci sono le emissioni provenienti dalle singole galassie e quelle del mezzo interstellare (Ims) all’interno della Via Lattea stessa. Il bello, però, è che questo lavoro di sottrazione di spettri di emissione lascia nelle mani degli scienziati un’enorme quantità di preziose informazioni.

Come quelle sulla mappa delle nubi di monossido di carbonio (CO) presentata a Bologna. Una delle fonti dell’emissione di primo piano catturata è rappresentata dalle nubi molecolari, le dense e compatte regioni della galassia, piene di gas, dove hanno origine le stelle. La maggior parte del gas che le compone è freddo idrogeno molecolare (H 2, ovvero due atomi di idrogeno legati insieme), che però non emette radiazioni facilmente e non è quindi rilevabile dalle strumentazioni. Per individuare queste nubi, allora, i ricercatori hanno deciso di cercare altre emissioni: quelle emesse dal monossido di carbonio, molto più raro rispetto all’idrogeno, ma più semplice da individuare, soprattutto dagli strumenti di Planck. Il risultato di questa scelta è la prima mappa del CO presente nella galassia e, di conseguenza, delle nubi molecolari della Via Lattea.

“ L’enorme vantaggio della mappa creata da Plank è che ci permette di trovare concentrazioni di gas molecolare dove non ci aspetteremmo”, spiega Jonathan Aumont, Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Universite Paris XI (Orsay, France). Questa mappa semplificherà il lavoro dei radiotelescopi terrestri, rendendolo soprattutto più mirato. Anche questi, infatti, sono sensibili alle emissioni di CO ma possono esplorare solo porzioni limitate di cielo. Ora gli scienziati sapranno esattamente dove puntarli.

Ma la maggior parte delle emissioni galattiche misurata da Planck non è quella delle fredde nubi quanto quella prodotta da elettroni liberi e dalla polvere presente nell’Ims.

Nel primo caso ce ne sono due diversi tipi - emissione di sincrotroni e radiazione di frenamento, o bremsstrahlung – entrambe molto intense alle frequenze più basse. L'emissione della polvere, invece, è più intensa nello spettro dell’infrarosso, individuato dai canali ad alta frequenza del telescopio.

A disturbare l'intercettazione della radiazione cosmica di fondo vi poi una quarta emissione, sempre intercettata da Planck, chiamata emissione anomala di microonde. Sono tutte e quattro semplici da identificare, perché presentano spettri abbastanza diversi.

C'è un però: non sono sufficienti a spiegare tutte le emissioni galattiche. Ciò che resta è quello che gli scienziati hanno soprannominato galactic haze: una sorta foschia che circonda il centro galattico, individuata con certezza grazie al Lfi, lo strumento italiano di Planck, e di cui già le osservazioni del telescopio Fermi della Nasa avevano fatto supporre l’esistenza.

Resta incerta l’origine di questa emissione. “ I dati che presentiamo alla conferenza mostrano che si tratta di un’emissione di sincrotroni, ma diversa da quella standard vista in altre aree della Via Lattea”, spiega Krzysztof M. Gorski del Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Jpl) di Pasadena (Usa) e dell’Università di Varsavia (Polonia). In particolare, questa emissione ha uno spettro più duro: spostandosi verso energie maggiori e quindi frequenze più alte, la sua intensità non diminuisce drasticamente, come avviene di solito. Ora gli scienziati sono a lavoro per capire il perché di questa differenza e le ipotesi sono ancora le più disparate: dalla maggiore frequenza di esplosione di supernovae al vento galattico, fino all’annichilazione di particelle di materia oscura.

Fonte: Wired.it

|